Portals and pipelines: How Rider recruits post-NIL

By Jake Tiger

A flight from New Jersey to Kansas typically takes five or six hours, but because it was his first time flying, Kevin Baggett said it felt like an eternity.

A highly touted basketball prospect in the mid ’80s, Baggett was heading west for a recruiting visit at prestigious Kansas University, far from his home in Burlington Township, New Jersey.

“I remember it vividly,” he said. “We’re still flying, and I’m sitting there saying to myself, ‘Man, do I really want to come across the country to go to a school and not have my family there?’”

Kansas had it all: world-class facilities and coaches, perennial NCAA tournament contention and future NBA All-Star Danny Manning as his host. But when it came time to decide, Baggett, a self-proclaimed mama’s boy, could not stomach living with a “host family” that would watch over him.

“[Kansas] introduced me to a host family, and they said this would be my family for the next four years. I’m thinking, ‘That doesn’t look like my mother,’” Baggett said. “I told them I can’t do that. I need to see the people that raised me.”

Baggett eventually chose to play college basketball at Saint Joseph’s in Philadelphia because of personal connections there, and he wanted to be close to home, but not too close, he said.

Four decades later, as Rider men’s basketball’s head coach of 12 years, he has used that same logic to attract talent from Pennsylvania, New Jersey and the rest of the Northeast.

However, the recruiting landscape has grown increasingly difficult to navigate for smaller, mid-major schools like Rider, since the NCAA-implemented name, image and likeness rights in 2021 allowing college athletes to sign potentially lucrative brand deals.

For players, continuity and team chemistry have fallen to the side, as many of them transfer multiple times to maximize their NIL money. Baggett said wealthier schools rarely even need to recruit anymore; they just need to offer the most money.

Today, the elaborate sales pitch Baggett received in Kansas is no longer a necessity. The basketball world he grew up in is gone.

Pipelines to prospects

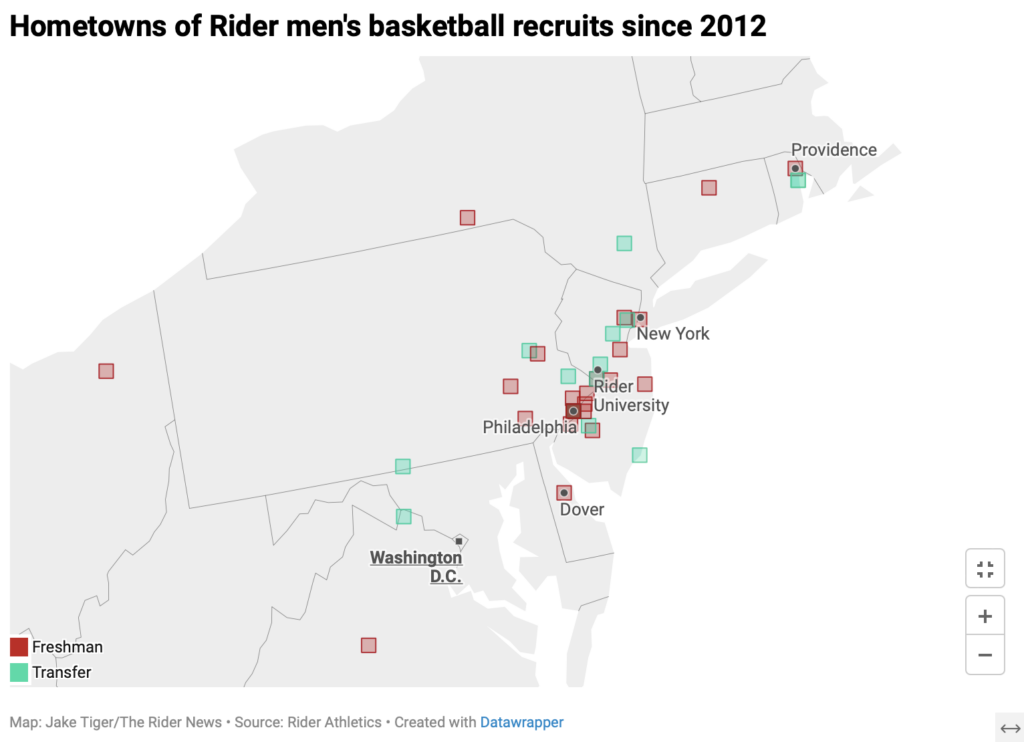

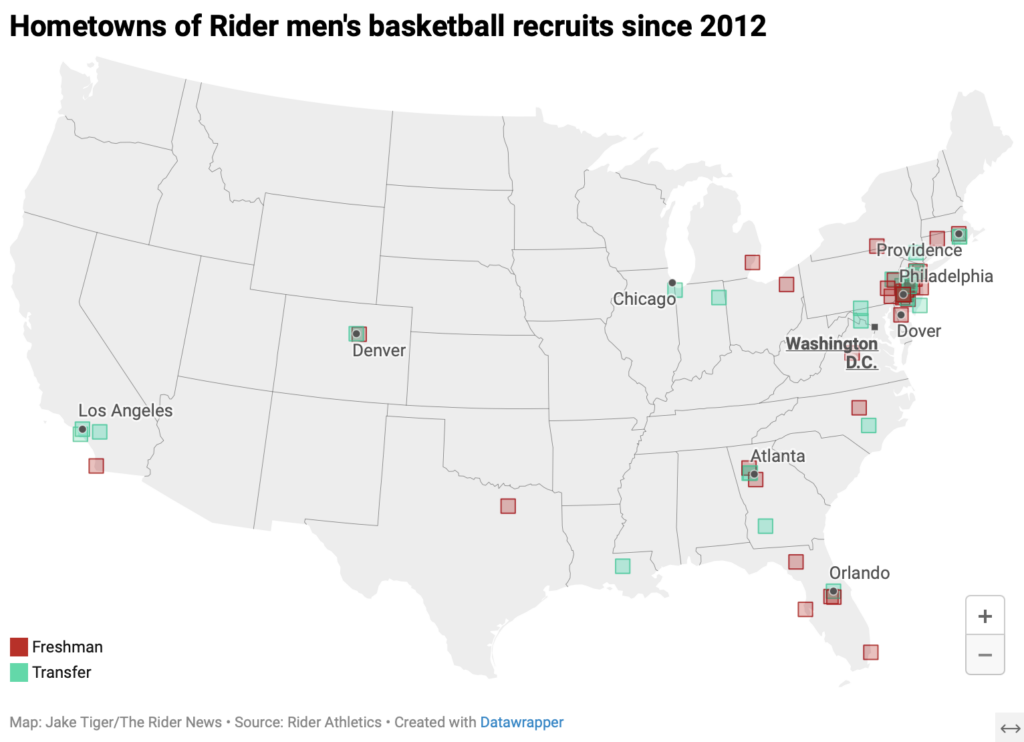

In Baggett’s 12 years as head coach, much of Rider’s recruiting success has come from the campus’ location, as 39 of Baggett’s 82 total players have come from New Jersey or Pennsylvania, where the Broncs have well-established pipelines.

One of Rider’s main selling points to prospective students is its nestling between two of the largest job markets in the country: New York City and Philadelphia. In recruiting, though, Rider’s sports teams cannot as easily leverage its proximity to the so-called “mecca of basketball.”

Atop New York’s skyscrapers, basketball prospects can spot universities like Iona, Saint Peter’s and Manhattan, all of whom are Metro Atlantic Athletic Conference rivals of Rider and much closer to home.

Rider has only had three players from all of New York in Baggett’s tenure, and the Broncs could only yank one player out of talent-laden New York City: Dimencio Vaughn ’22, a gritty, two-way wing at Rider for five years. When quizzed, Baggett immediately identified Vaughn as his only player from the city.

“Oh man, if I could have another Dimencio Vaughn, I’d take that in a heartbeat,” Baggett imagined, leaning back in his chair and looking up at the ceiling.

According to Baggett, Vaughn only ended up in Lawrenceville because Rider had connections with his childhood coaches and built a relationship with him early on. With other New Yorkers, Rider has not been so lucky, and it has, instead, honed in on Philadelphia, which “just has tougher kids,” according to Baggett.

The Broncs have deep ties within Philadelphia, and Rider is the only MAAC school within an hour of the city, making it the perfect pipeline.

In Baggett’s term, Rider has recruited 16 players from Philadelphia alone, matching New Jersey’s total.

While Baggett played at Saint Joseph’s, much of his staff also has a history in the city, including Associate Head Coach Dino Presley, who coached at Drexel and has worked with Baggett for 10 seasons.

“Rider has always recruited Philly, even before I got here,” Presley said. “We don’t really need to go anywhere else because that’s our base. We can get a kid out of Philly every year.”

Rider’s local relationships have also been helpful in the NCAA transfer portal, which allows athletes to change schools between seasons.

Take junior guard Andre Young and senior forward Tank Byard: both players transferred to Rider for the 2024-25 season because of high school connections.

According to Baggett, Byard is from Atlantic City, New Jersey, and Rider scouted him years ago. Young was “hand-delivered” to Rider by the head coach of Georgia’s Pebblebrook High School, where Rider has plucked talent from for years: Dwight Murray Jr. ’23, Mervin James ’24 and Kami Young, who transferred out of Rider in 2023.

Baggett said a pipeline out of Rider has also developed in Norfolk State, who poached Rider’s Christian Ings in 2021, and Allen Betrand and Tyrel Bladen in 2023 via the transfer portal – a booming, volatile fixture of college athletics.

Portals to prosperity

According to NCAA data, 17,781 Division I athletes entered the transfer portal in 2021. In 2023, there were 23,021.

The transfer portal’s rapid growth is partially due to the introduction of NIL rights in 2021, allowing many college athletes to profit off of their celebrity. Overall, though, the culture surrounding the transfer portal has changed, as hopping to a new team nearly every season has become the norm for many players — just ask Baggett.

“I do believe that, more often than not, kids make these decisions for all the wrong reasons,” Baggett said.

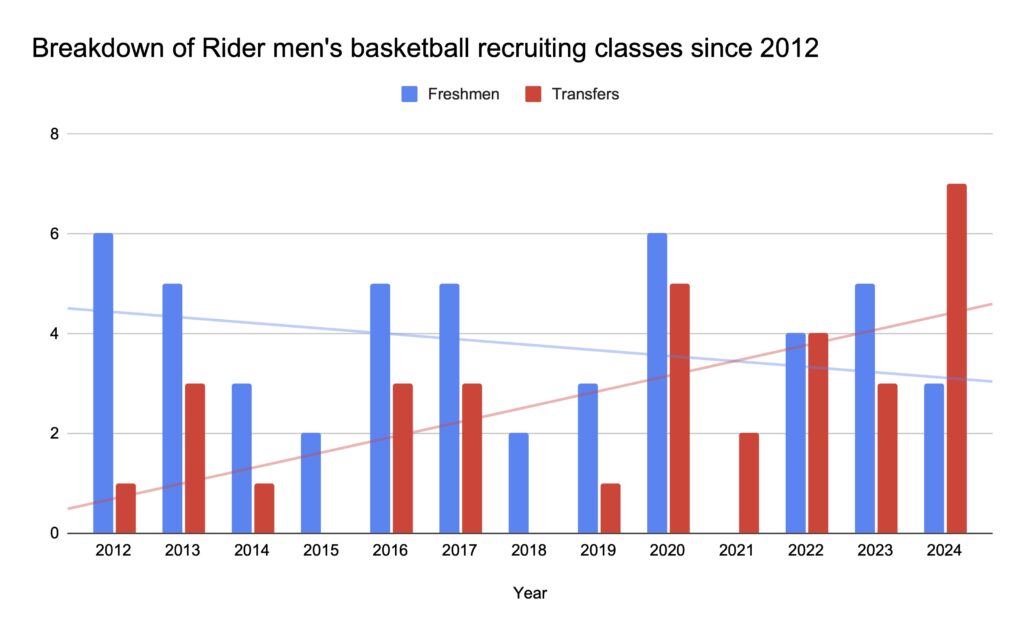

From 2012 to 2020, freshman recruits were the primary way Baggett built his teams: 37 freshmen compared to 17 transfers in that span.

After 2021, however, the trend flipped with Rider bringing in 12 freshmen and 16 transfers. In the last four years, Baggett has had nearly as many transfers as he did in his first nine seasons.

Baggett described a modern team-building landscape of “haves and have-nots” created by NIL, where schools like Rider struggle to compete with programs that can simply throw money at recruits.

“There is value to NIL, but some of the money these kids are getting paid is outlandish,” Baggett said. “I don’t know how coaches coach players that are making more than them. … We’ve just really lost our way. The NCAA dropped the ball on this entire thing.”

Rider used to punch above its weight when recruiting, going out early and forming bonds with high-level prospects – like Vaughn – but, since NIL’s advent, it all comes down to dollar signs, Baggett said.

Baggett also noted that rampant transferring in pursuit of NIL money can have effects in the classroom, as student athletes bounce between schools, each time losing the continuity they had with professors and classmates.

“The more kids transfer, the less kids are going to get their education,” he said. “Our sport … there are a lot of Black athletes, and that’s just that many more Black athletes that won’t be getting their education.”

At the same time, Baggett understood why modern student-athletes are so concerned with money; he admitted he “absolutely” would have committed to Kansas if NIL opportunities were a factor back in 1985, and understandably so.

According to an April report from 247Sports, Kansas men’s basketball players collectively made $4 million during the 2023-24 season, the most of any college basketball team. That’s an average of almost $250,000 for the team’s 17 players.

Baggett said, at a MAAC basketball meeting, the conference told coaches the entirety of the MAAC should offer $250,000 in NIL money combined.

Rider’s student-athletes can make NIL money through MOGL, an NIL platform Rider partnered with in 2023 that helps schools connect with brands and allows student-athletes to become a sort of freelance influencer.

On MOGL, partners can select from dozens of Rider athletes, each with a starting rate of $10. Most players have a photo, short biography and social-media-follower totals linked to their profiles to show how influential they are.

Student athletes can be sorted by gender, follower count, sport and other criteria.

Partners can ask for video shoutouts, appearances at events or special requests. They can also leave star ratings on athletes; some athletes boast a five-star rating but most do not have a rating at all.