Requiem or rebirth: the Westminster saga

Kaitlyn McCormick

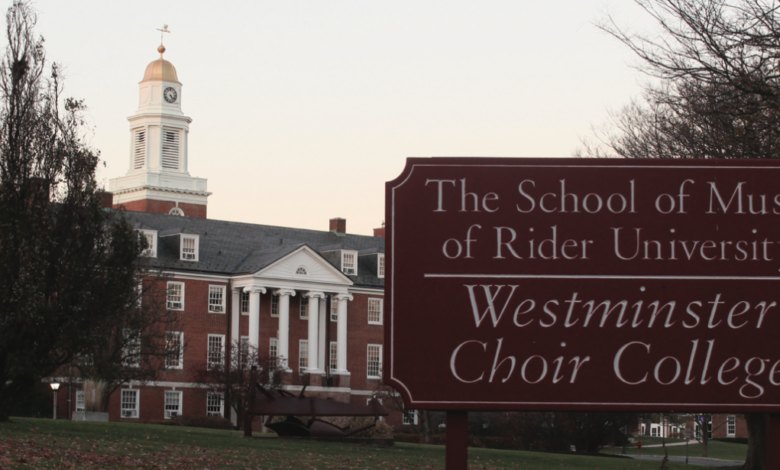

Pink dogwood trees blossomed in the spring, framing robust windows from which beautiful music would once flow out into the quad of Westminster Choir College (WCC) and into the surrounding Princeton area. Now, 101 Walnut Lane sits shackled in silence.

Since initial moves by Rider President Gregory Dell’Omo’s administration to sell the college and campus in 2017, the past five years have been shrouded in concern, confusion and a bevy of unanswered questions from WCC students, faculty and supporters as some cling to the hope of reverting to a pre-Dell’Omo era and others look to the future to rebuild.

“To hear it quiet like this is like standing in a tomb,” said composition and music theory professor Joel Phillips as he walked the abandoned campus quad on a recent fall day. According to Phillips, the location is so meaningful that the campus founders and even some alumni have had their ashes scattered over the greenery, vibrant in the late afternoon sun.

Phillips is just one of the many professors worried about the future of WCC. After Dell’Omo’s bid to sell the college to a China-based company collapsed, he embarked on a new plan to move WCC to Rider’s Lawrenceville campus and sell the valuable Princeton property. As a result, since Rider first announced plans to sell WCC in March 2017, a public saga has unfolded, burdening choir students and faculty alike.

Tides change under Dell’Omo

When Dell’Omo started his tenure with Rider and subsequently his relationship with WCC, “he kind of came to campus swinging,” said Phillips.

In a February 2015 interview with The Rider News predating Dell’Omo’s official start at the university on Aug. 1 of that year, he described WCC as a “jewel” and lauded its history and international reputation. “You don’t want to water it down in any way so it can stand out on its own,” he said.

But quickly, things changed.

In December 2016, Dell’Omo’s initial idea to move WCC to Lawrenceville and sell the Princeton land was met with fierce opposition from students, faculty and alumni.

“If you had dropped a bomb on this campus, it would not have had as big an impact,” Phillips said.

Just three months later, Dell’Omo announced that both the famous choir college and campus were up for sale. When that effort failed, Dell’Omo moved WCC to Lawrenceville and tried to sell the land.

The process to sell the property is one that has quickly become riddled with lawsuits from students and alumni as well as from the Princeton Theological Seminary to block the attempted sale.

In March 2020, New Jersey Superior Court Judge Robert Lougy granted the motion to dismiss the lawsuits, indicating that the parties lacked grounds to sue. An appeal was heard in May 2022, and was still pending six months later.

The Princeton Theological Seminary’s 2018 lawsuit against Rider, arguing that it has beneficiary rights to the land, is also pending.

While an eager community waits for a decision, the campus remains in use by the Westminster Conservatory of Music, a community music school under the direction of the university. Rider also renewed a deal with the Princeton Council this year to lease a portion of the campus’s vacant parking lot for just $2,000 a month.

On Sept. 6, the Westminster Foundation announced ML7, a real estate and investment firm, as a potential buyer interested in both the college and Princeton property, though the proposed sale remains at a standstill until court proceedings have ended.

Associate Vice President for University Marketing and Communications Kristine Brown said at the time, “Rider has received many inquiries as to purchasing the Princeton property, including from ML7, but is not in a position to sell until the litigation being pursued by the Princeton Theological Seminary is resolved.”

Financial struggles pose university changes

In a written statement provided by Brown this week, Dell’Omo explained the administration’s decision to move WCC: “When it was independent, WCC almost never was able to support itself. It was on the verge of closing in 1991 when Rider took it over and Rider has been underwriting its losses for almost 30 years. The decision to merge the campuses in 2020 was done for sound financial reasons for the greater good of the entire institution as well as to provide the opportunity to create new academic program synergies.”

Many have criticized the attempted sale as a means to help supplement Rider’s cash deficit, as the university has implemented major restructures and prioritization methods to stabilize the university’s future, recently including the elimination or archival of 25 programs, a number of which fell under WCC.

On the program cuts, Associate Dean Jason Vodicka, who started the position following the College of Arts and Sciences restructure in March and oversees WCC, explained that while certain degree programs have been eliminated, students can still utilize the college’s bachelor of arts in music degree to create their own focus area of study.

“We can do all the same things. It’s just that the degree itself might look a little different,” said Vodicka, who is an alumnus of WCC.

Part of that different look is the likely loss of longtime WCC faculty.

On Oct. 31, Provost DonnaJean Fredeen delivered a layoff notice to the Rider community via email, mentioning that while there was not yet a need to eliminate any full-time faculty, six adjunct professors were let go, though it has not been released how many were WCC.

“This work is currently ongoing and decisions will be driven largely by enrollment,” the email read.

Fredeen canceled an interview with The Rider News scheduled for Nov. 29.

Under these new changes, faculty were also offered a bid for early retirement. Composition and music theory professor Jay Kawarsky decided to take the deal and will be ending his almost four- decade-long tenure with WCC in June of 2024.

“I look at, even in the next year and a half, how many new students am I going to have for a freshman class?” Kawarsky said in an interview with The Rider News.

The choir college’s enrollment has been on a steady decline since 2007, with a precipitous drop starting in 2016 – the time of Dell’Omo’s proposed sale.

In 2016, WCC had 72 full-time freshmen. This year, there are only 18 – a 75% decline, sparking even greater concern for WCC’s future and the programs that remain.

Dell’Omo wrote, “We are working hard in our recruitment efforts for WCC, but, as with all academic programs at the university, we must continually evaluate their success and sustainability.”

Vodicka explained that the university has been developing a more focused advertising campaign and increased spending to boost enrollment, which will in turn benefit WCC, as well as catering to specific journals and periodicals that are popular amongst music students and teachers.

WCC also hopes to spark enrollment through its annual choral invitational in March, which was previously on hold due to the pandemic.

In years past, WCC choirs have famously performed alongside groups like the New York Philharmonic and the Philadelphia Orchestra. In 2012, the Westminster Symphonic Choir performed at Carnegie Hall alongside the Berlin Philharmonic.

Phillips shared that challenges to enrollment pose a threat for the large symphonic choir to perform to this caliber due to a lack of participants.

Vodicka said the college is still providing students with unique opportunities, continuing its tradition of working with different conductors, expressing the importance of students being able to network with professionals in the business and experience various perspectives.

On Nov. 20 the Symphonic Choir performed El Mesías: Handel’s Messiah for a New World in New York with guest conductor Ruben Valenzuela, founder and director of Bach Back Collegium San Diego.

Students caught in the crossfire

After years of turmoil, change and reductions at WCC, many students’ experiences have strayed from their original expectations.

Music theory and composition major Charlie Ibsen, who graduated in May, was a member of the last class who got to experience the Princeton campus before the COVID-19 pandemic even further derailed WCC students’ time in what he described as a “perfect little haven of choral music.”

“I think that the drama with the consolidation and then the sale and then the cancellation again. It absolutely put a nasty spin and kind of bitter taste on at least the last three years,” Ibsen said.

The alumnus drew inspiration from the chaos that surrounded his undergraduate experience, composing a five-movement choral piece for his senior thesis, entitled “Spectemur Agendo,” the college’s motto and Latin for “let us be judged by our deeds.” He interviewed dozens of alumni and focused on the history of the school.

Ibsen explained that the piece is written in the style of a requiem, traditionally a Latin mass for the dead. “In most composers’ cases, they’re writing requiems for other people, but I wrote one for what I was mourning,” Ibsen said.

Junior music production major Bela Nakum, who uses the pronoun they, started their WCC experience on the Lawrenceville campus, a new path from the childhood they had spent on the Princeton campus attending lessons at the Westminster Conservatory and High School Vocal Institute, a program sponsored by the college’s continuing studies program that is popular amongst future WCC students.

Though music production is technically not a WCC major, Nakum spent their freshman and sophomore years in WCC and is still involved in multiple choirs that are also open to Rider students,including Jubilee Singers.

“Most people in the class … that I entered Westminster with were aware of the situation with the campuses … the few people who weren’t awarebecame aware pretty quickly,” Nakum said.

Senior music education major Rachel McNamara is a prime example; despite knowing the issues surrounding the campus, McNamara still made thechoice to transfer to WCC her sophomore year, but she nonetheless shares some of the disappointments and worries expressed by other students.

While she expressed positives like the ability to meet more friends at Rider or take different courses, it’s still “disappointing,” McNamara said, “to not have the community that the Princeton campus facilitated.”

Adapting to Lawrenceville

On the future of WCC, Vodicka says he’s afraid of a “self-fulfilling prophecy,” when it comes to the concern surrounding the choir college.

“I think it’s really important that all of us faculty, administration, alumni, that we put our efforts into getting students back to Westminster and to experience some of these opportunities that we are able to provide for them,” Vodicka said.

Dell’Omo wrote, “Rider would welcome resounding support for WCC in Lawrenceville from faculty, alumni and other WCC supporters to help build enrollments. Unfortunately, negative publicity and lawsuits only serve to damage enrollment efforts.”

Last spring, a number of students and alumni filed a petition with Rider administrators to air grievances about the change in campus, including mainly issues in facilities.

Vodicka maintains that efforts have been made in improving the quality of the Lawrenceville facilities, including fixing issues with the Gill Chapel rehearsal space and utilizing the Student Recreation Center seminar room as another rehearsal space.

Though students like McNamara still find that the facilities and spaces dedicated to WCC students and choirs are lacking in comparison to the Princeton campus, which included the Hillman Performance Hall, part of the Marion Buckelew Cullen Center that WCC built in 2014 for $8.5 million.

An uncertain path forward

On the upheaval surrounding the move from the beloved Princeton campus, Vodicka said it’s something he chooses not to focus on: “It really is out of my hands,” he said.

Instead, he said he remains centered on providing students with a good WCC experience and striving to grow the college’s enrollment. “That’s where I’m choosing to focus my time and energy because I think that’s where I can make an impact … As far as the courts go, we’ll see where things land, but I’m dedicated to Westminster no matter where it is,” Vodicka said.

However, the handling of the campus consolidation has inarguably left what Ibsen called a “bitter taste” in the mouths of many in the WCC community.

McNamera said, “It could have been acknowledged that our grief and frustration was warranted.”

Ibsen added that Rider’s administration has consistently disregarded WCC’s students, faculty and alumni: “It’s interesting to think about just howintensely you have to ignore … hundreds of people and decades of history. You have to be so good at tuning it all out.”