The privileges of being white passing

By Tristan E. M. Leach

When I began applying for colleges, there would always be the section on the application where you were supposed to check off ethnicity. This portion of the application always felt a bit awkward to me. I would check white, Filipino and Alaskan Native. But I knew no matter what, I would reap the benefits of looking like my dad, a white man.

From a young age, I became aware of the privileges of being white passing. As young as third grade, peers were telling me that my mom couldn’t possibly be my mother. At first it didn’t really bother me; children don’t often conceptualize these issues. I was aware of racism, I just didn’t know how it was affecting my mother at this point in my life.

That all changed when I was 10 years old. My dad and I were going into a town to pick up my birthday cake, when my dad told me we couldn’t go the usual path we would. When I asked him why, my dad responded, “There are some really mean people who are protesting people who look like mom.” I was shocked. What had my mom done to these people? What had Filipino people done to these people?

The answer? Nothing.

As I grew up, the privileges of being white passing became more obvious to me, and I was beginning to reap the benefits. I was never followed home like my younger brother. I never had to listen to people continually guess “what I am” as my sister has. When I attended high school for musical theater, there were an infinite amount of roles for me. I was a minority who was lucky enough to be automatically included in the majority. There was no way for me to proudly show what my mom had given me.

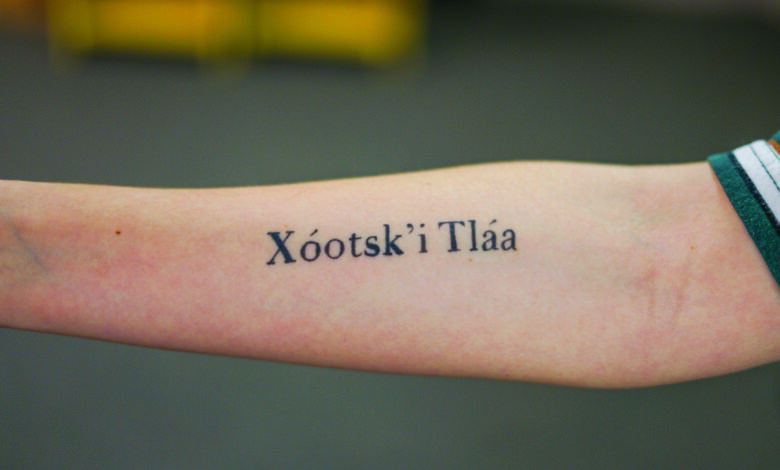

When I was born I received two middle names: Elizabeth, for my great grandmother, and Malulani, Hawaiian for “protected by God.” My mom grew up on the big island of Hawaii in extreme poverty. I was always upset, because on school identification cards the “E” was the only middle initial used. I felt as if a part of me was being erased. A few months after I was born, I was given my Tlingit Alaskan Native name: Xóotsk’i Tláa.

Though those names were a part of my identity, it was not clear, so when I was old enough to get tattoos, I decided that I would make my identity known. I started with Malulani on my left arm, and then a few months later I got Xóotsk’i Tláa on my right. The tattoos have sparked conversations, and I am proud to bring light to issues that both Hawaiians and Native Americans face.

However, it is important to note that I do not know everything about what Native American peoples face everyday.

Our country treats the first inhabitants of this land as if they were not here first. “But native peoples have casinos!” Well, yes, but also no. Native American peoples rarely make enough money to support themselves.

Reservations rarely have running water, and food is at least two times more expensive there than it is on non reservation land.

I know that I have privilege because of how I look. I know it’s important to acknowledge that privilege and every benefit I have reaped from it.