Speaker unpacks sports’ slow adoption of social change

By Caroline Haviland

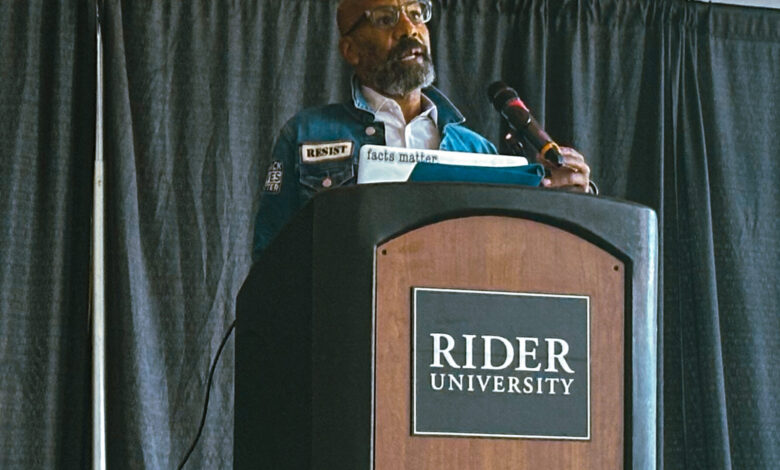

Kevin Blackistone stood before a crowd on Oct. 17, as students sat ready to hear his remarks on the prevalence of sports in culture and how, contrary to popular belief, it is not the engine for social change that many believe it to be.

“We have, for a very long time, forded sports this idea that it is in the vanguard of social change. That is not necessarily true,” said Blackistone.

A projector screen hung above him, reading, “The Myth of Sports and the Myth-Making of Sports Journalism.”

Blackistone has spent his career studying this topic, and observing in his childhood. He grew up a fan of Washington’s NFL team, which only recently changed its culturally insensitive name.

Owen McCarron, a junior radio and podcasting major, introduced Blackistone at the event.

“As sports continue to grow, and so does the course of the world, it is crucial to maintain a level head and stay educated on matters that are greater than who bought off the refs and why the Jets can never win a Super Bowl,” said McCarron.

Blackistone, an award-winning sports columnist at the Washington Post, an ESPN panelist and a professor at the Philip Merrill College of Journalism at the University of Maryland, came to Rider to “demythify” the narrative told in sports journalism.

The story starts with a familiar name in the sports world: Jackie Robinson.

‘America’s pastime’

Baseball has commemorated Robinson as a pivotal point of desegregation in the U.S. His jersey number, 42, was retired by the MLB in 1997, and April 15 was declared Jackie Robinson Day. What sports media has left out of this foundational story, according to Blackistone, is what happened to “the Jackie Robinsons before.”

Prior to Robinson stepping up to the plate, Moses Fleetwood Walker joined the Toledo Blue Stockings in 1883 as the first African-American player in Major League Baseball. Blackistone said Walker’s participation faced resistance from an influential figure in 19th century baseball, Cap Anson, whose protest “drew the color line,” which many adhered to for decades afterward.

“We the media have told you that Robinson was the first Black man to play Major League Baseball and we the media rarely, if ever, tell you the story about Fleetwood Walker and Cap Anson,” said Blackistone. “America’s pastime is watching the game in which the only people allowed are white men. One of the most marvelous flips of a script in history.”

Robinson’s integration in 1947 was part of a lineage of events from the Civil Rights Movements of the 1940s. His story adds to the notion that sports has been a slacker rather than a leader in racial justice.

‘White-washed’ journalism

Sports journalism in the U.S. began in 1819 with the American Farmer Magazine, the first periodical dedicated to sports. The publication sparked numerous others over the following 15 years, all of which were owned and operated by white men.

“Thus laid the racial roots for sports journalism in the U.S.,” said Blackistone, “which was and continues to be mostly white men interpreting the performances of Black athletes.”

Blackistone provided an example of sports journalists supporting racist stereotypes based on a study conducted in the second half of the 20th century. Black athletes have been perceived in the media by their natural athletic ability, such as Michael Jordan being applauded for his “athleticism,” while white athletes are described by their intelligence, like Larry Bird for his “brilliant plays.”

The racial injustice in sports is identifiable apart from the discrimination of players. The appropriation of native culture and imagery for team names, mascots and logos has been “white washed” more in sports than in any other corner of society, said Blackistone, such as the Kansas City Chiefs in the NFL and the Chicago Blackhawks in the NHL.

“You can’t talk about systematic racism in this country without understanding what happened to the native people here after [Columbus] touched these shores,” said Blackistone. “Sports washing did not begin with golf. It’s been around for a long time.”